The World's First Hack: the Telegraph and the Invention of Cyber Privacy

Concern over personal data interception did not start with GCHQ and the NSA, hacking can be traced all the way back to the 19th century

The Telegraph Museum in the Cornish village of Porthcurno hosts the Cooke-Wheatstone device used to catch murderer John Tawell. John Tawell had money worries. The £1 weekly child allowance he had to give his mistress Sarah Hart was the last straw, and on New Year’s Day 1845 he travelled to her house in Slough, poisoning her beer with a potion for varicose veins that contained prussic acid.

After the murder, Tawell made his escape on a train headed to London’s Paddington station. He wasn’t known in Slough and expected to slip through the hands of the law. But he was travelling along one of the only stretches of railway in the world to have telegraph wires running beside the railway lines.

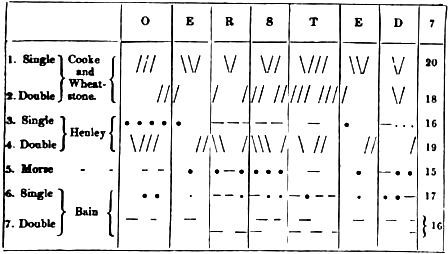

Tawell was a Quaker and had been dressed in a distinctive dark coat. A witness, Reverend ET Champnes, had seen Tawell leaving the crime scene and followed him to Slough station, but not in time to stop the train. Champnes found the stationmaster and together they sent a message to the police in Paddington. Pre-dating Morse code, only 20 letters could be covered by the early telegraph system, and Q wasn’t one of them.

“A MURDER HAS GUST BEEN COMMITTED AT SALT HILL AND THE SUSPECTED MURDERER WAS SEEN TO TAKE A FIRST CLASS TICKET TO LONDON BY THE TRAIN WHICH LEFT SLOUGH AT 742 PM HE IS IN THE GARB OF A KWAKER WITH A GREAT COAT ON WHICH REACHES NEARLY DOWN TO HIS FEET HE IS IN THE LAST COMPARTMENT OF THE SECOND CLASS COMPARTMENT,” the message read.

It took police a while to work out what a KWAKER was, but they eventually apprehended Tawell. After a trial, he was executed in front of 10,000 people; the best advertisement possible for the telegraph’s speed and security.

The Times reported: “Had it not been for the efficient aid of the electric telegraph, both at Slough and Paddington, the greatest difficulty, as well as delay, would have occurred in the apprehension.”

The story of Tawell’s capture jump-started the rollout of the telegraph, signaling the beginning of sweeping social change brought about by technology. Companies began to tap into the public interest around that technology, and within four years, 200 telegraph stations had been connected in Britain. By 1858, the first successful test of an undersea cable between Europe and North America was made. By 1870 a telegram could be sent from London to Bombay in a matter of minutes.

The telegraph and privacy

For the vast majority of human civilisation, the scope of day-to-day conversational privacy had pretty much been whatever was beyond earshot. But the rise of the telegraph meant that the possibilities of communication exploded; by the mid-19th century you could go to a telegraph station and have a message sent further and faster than had ever been possible. The whole idea of what was “beyond earshot” changed inexorably. Along with that expanded space of communication came a newfound vulnerability. Words could be snatched from you long after they’d left your vicinity. Electrical telegraph lines could be tapped, signals intercepted. Cable workers were required to sign confidentiality agreements, but even they could be bribed to divulge messages.

Message security increased with the onset of coded languages. The Cooke-Wheatstone device used to catch John Tawell is on display at the Telegraph Museum in the Cornish village of Porthcurno, in the far south west of the UK. Its ornate, diamond-shaped console looks more like a Ouija board than a telecommunications hub, but soon became obsolete with the spread of Morse code. Not only could Morse account for all the letters of the alphabet, the system of dots and dashes meant that only those who understood the code could read the messages; namely trained operators.

As the telegraph expanded, so did the idea of conversation privacy. “By the turn of the century, business users were concerned about privacy, and cable companies were therefore keen to ensure they knew anything sent by cable was secure,” says John Packer, honorary curator of the Telegraph Museum and a lecturer from the museum’s previous life as a telegraphy teaching school.

Packer says that although the high cost of sending messages prevented people from exposing their personal lives, businesses increasingly expected sensitive communications to remain private and secure. Like today, this took the form of encryption. To keep information from prying operators, messages already encoded in Morse could be further encrypted with a cipher – an algorithm consisting of a number of steps to turn plaintext to cipher text. Tactics like this, along with the difficulties of tapping undersea cables, helped to keep messages from falling into the wrong hands.

By the end of the 19th century, the telegraph had evolved to become the dominant – and first – technology of mass communication. The Eastern Telegraph Company, with a global hub in Porthcurno, absorbed a stream of companies connecting the British Isles to everywhere from South America to India, forming a near-monopoly over international communications.

Telecommunications security had spread across the globe, but it wasn’t until a rival technology appeared that communications privacy was fully articulated as a concept within the public imagination.

Privacy: a brand new concept

Within a generation people had gone from worrying about what was heard within earshot to dealing with the potential for global interception through a complex electrical communications system. The sense of individual privacy developed rapidly, and by the start of the 20th century, the telegraph company had begun to leverage this relatively new concept to make sure competing technologies didn’t cut into its profits.

One such emerging technology was wireless transmission, which was being developed by Guglielmo Marconi, also in Cornwall, near the village of Poldhu. His work worried the Eastern Telegraph Company so much that it employed Nevil Maskelyne – a London magician known to use the nascent wireless technology as part of his mind-reading act – to disrupt it.

“By relaying my receiving instruments through landlines to the station in the valley below I had all the Poldhu signals brought home to me at any hour of the night or day,” Maskelyne boasted in The Electrician, where he published the intercepted messages and underlined the threat to privacy posed by wireless.

According to Packer, it wasn’t until Marconi’s experiments became technically feasible that privacy was taken as a selling point for the wired telegraph. “It wasn’t until that point that there was a need to publicise the advantage of using a cable, because prior to that there was no rival: you sent it by cable or you didn’t send it,” he says. The telegraph had done more than label a standard of privacy; it had helped to create the entire concept.

Maskelyne followed his trick with an even bigger showstopper. In June 1903, Marconi was set to demonstrate publically for the first time in London that Morse code could be sent wirelessly over long distances. A crowd filled the lecture theatre of the Royal Institution while Marconi prepared to send a message around 300 miles away in Cornwall. The machinery began to tap out a message, but it didn’t belong to the Italian scientist.

“Rats rats rats rats,” it began. “There was a young fellow of Italy, who diddled the public quite prettily...” Maskelyne had hijacked the wavelength Marconi was using from a nearby theatre. He later wrote a letter to the Times confessing to the hack and, once again, claimed he did it to demonstrate the security flaws in Marconi’s system for the public good.

Maskelyne may have been in the pocket of the Eastern Telegraph Company, but his exposure of security weaknesses has a lot in common with contemporary hackers and cybercriminals who set it upon themselves to find and brandish security flaws.

As the amount of data transferred over telegraph increased, security measures and concerns also grew. Of course, that data is nothing compared to what we transfer today, both wirelessly and through fibre optic cables. With almost every aspect of our lives now passing through telecommunications systems, the level of concern about privacy and security has grown to become one of the most pressing issues of our age.

GCHQ and mass interception

On Cornwall’s north coast is the seaside town of Bude, home to GCHQ’s satellite ground station co-operated by GCHQ and the NSA. GCHQ Bude’s satellites are thought to cover all the main electromagnetic frequency bands. In 2013, the Guardian reported that the government site had also been monitoring probes attached to transatlantic fibre-optic cables where they land on British shores in west Cornwall. According to the report, in 2011 there were GCHQ probes attached to more than 200 internet links, and these were each carrying data at a rate of 10 gigabits a second.

The Guardian report claimed that GCHQ’s ability to tap into fibre optic cables consequently gave GCHQ and the NSA access to enormous quantities of communications, including records of phone calls, Facebook posts, internet history and email messages.

“Despite the current furore over hacking, which is only a modern term for bugging, eavesdropping, signals intercept, listening-in, tapping, monitoring, there has never been guaranteed privacy since the earliest optical telegraphs to today’s internet,” Packer says. “There never was and never will be privacy.”

The horizon of white dishes and orbs of GCHQ Bude is on a completely different scale to the interception aerials used by Maskelyne, yet they too loom behind the barbed fences on a Cornish shore like the props of a magician.

When John Tawell travelled from Slough to Paddington, his pursuers were able to use the telegraph to send a message faster than the train he rode on. T

oday, location tracking would allow authorities to trace Tawell’s smartphone to within a few metres, his search engine history could be flagged up for inappropriate terms, his messages with Sarah Hart intercepted, extracted, pored over and stored. He could be arrested before he even woke up.