Defusing The Internet Of Things Time Bomb

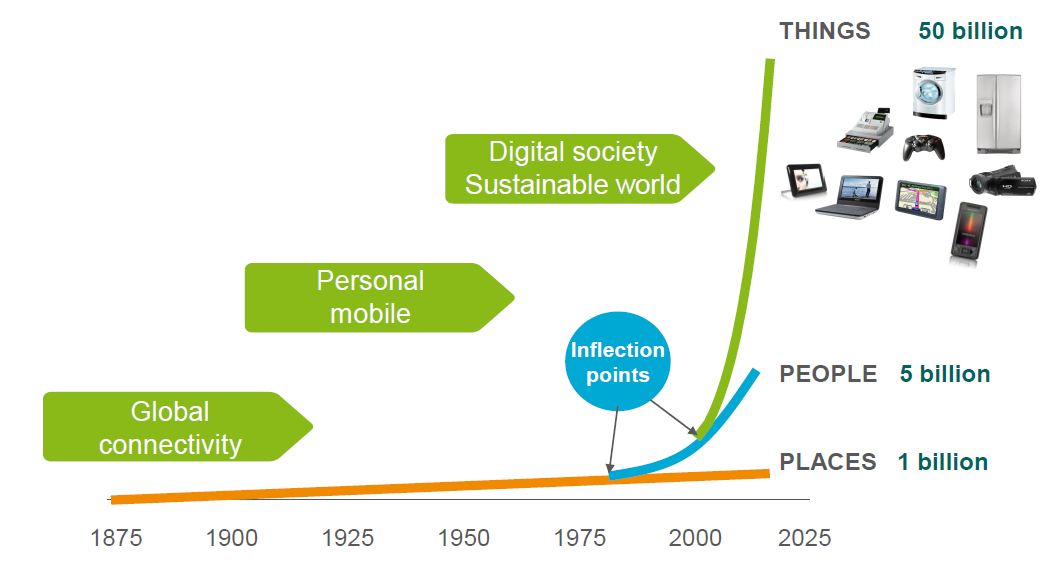

They’re coming, and we won’t be able to stop them. But will they be friends or foes? We are we talking about the Internet of Things (IoT) devices. And, as with most things, the answer will depend on the details. Gartner predicts there will be approximately 5 billion such devices in use this year, growing to 25 billion (more than half of them consumer-focused) by 2020.

“Smart” devices are the buzz, whether in the connected home (thermostats, light bulbs, garage door openers, locks and various appliances) or new wearable devices. They promise convenience along with improved control and efficiency in our lives. But, as highlighted by the recent hacking of automobiles, connectivity can come at a significant cost.

Consumers cringe as the barrage of data breaches continues — from major retailers to health insurers to government agencies, hundreds of millions of records are now exposed and there seems to be no end in sight.

Will we face a similar future with some of our most personal and sensitive information (where we are, the status of our home, our latest health vitals), or even with our physical security?

The consequences range from annoying (lights turning on and off, coffee makers starting up in the middle of the day) to creepy (messages on a smart refrigerator, locations being tracked, cameras being hijacked) to downright dangerous (thermostats/appliances being manipulated to the point of physical damage or fire, locks and garage door openers being compromised).

These issues are the focus of the Internet of Things Working Group (IoTWG), recently established by the Online Trust Alliance (OTA), a non-profit focused on the establishment and adoption of best practices that enhance online trust.

The IoTWG is made up of dozens of organizations, including leading retailer Target and technology leaders Symantec and Microsoft. Its mission is to establish a trustworthy framework for IoT manufacturers to follow that addresses three key pillars: security, privacy and sustainability.

IoT offerings present a unique challenge because of the balance between functionality and connectivity.

Many of these recommendations have their foundation in the OTA Online Trust Audit, a review of security, privacy and consumer protection practices enacted by 1,000 leading retailers, banks, social networks and government websites. In fact, in the 2015 OTA Audit, the websites of the top 50 IoT manufacturers were evaluated for the first time; the scores were not encouraging, with a failure rate of 76 percent.

This research highlights the need for increased vigilance and focus on security and privacy by design in this rapidly emerging market.

IoT offerings also present a unique challenge because of the balance between functionality and connectivity (e.g., does the connectedness of your coffeemaker have any impact on its use to make coffee?), the nature of their interconnectivity (e.g., how much should devices be evaluated as standalone versus in the context of overall use, as in a connected home?) and the long-term nature of their use (e.g., how to deal with the “smart” nature of home devices long after the warranty has expired).

In the security arena, many of the IoTWG’s recommendations complement widely accepted standards and practices in place today, including encrypting data in transit and at rest using current best practices, using randomly generated usernames/passwords, using Always-On SSL or other appropriate methods to protect session data and mechanisms that ensure updates and consumer notification are not sent from fraudulent sources.

What complicates the landscape is that the majority of devices are dependent on apps, mobile platforms and back-end cloud services that often integrate with “home automation hubs” — all of which can become an attack vector for any new devices added to the network.

Suggested IoT privacy practices parallel those in place today for general web services, yet the sensitivity of IoT data tied directly to an individual and the form factors used present additional challenges and concerns.

Key recommendations here include sufficient notice in a format consumers can easily access (preferably before purchase), limitations on data sharing with third parties (who may be integrally involved in delivering the service), data retention policies and clearly defined implications of a customer’s refusal to accept a privacy policy (e.g., how much of my smart TV is usable if I don’t accept the policy?).

Perhaps the most concerning issue is the ticking time bomb of sustainability, or ensuring IoT devices remain secure long-term, throughout their entire life cycle. New paradigms are present here — who would have previously considered software upgrades for garage door openers or washing machines that might impact security or privacy?

Contrary to the mobile device market, which has a relatively short half-life, the useful life of IoT devices, especially in the home, is much longer. The concept of “security and privacy by design” for manufacturers is critical here — they must take a long-term view of the offerings in the context of overall use, designing products and services that can keep pace with security and communication protocols that evolve over time.

Key issues include support timeframes (e.g., how long will the software/service be supported, even if the device is long out of warranty or has been replaced by newer models), compatibility issues (e.g., if an upgrade causes incompatibility, can I roll back?) and functionality in light of connectivity or policy issues (e.g., what still works on my smart device if it’s not connected, and what still works if I don’t do an upgrade or refuse to accept an updated privacy policy?).

Working through all these issues now allows manufacturers to incorporate the concepts into the design of products, services and associated policies, thereby helping to protect consumers from potential abuse and harm.

The framework is intended to serve as a foundation for any IoT certification program that might be considered.

Techcrunch: http://http://tcrn.ch/1UzCkhm